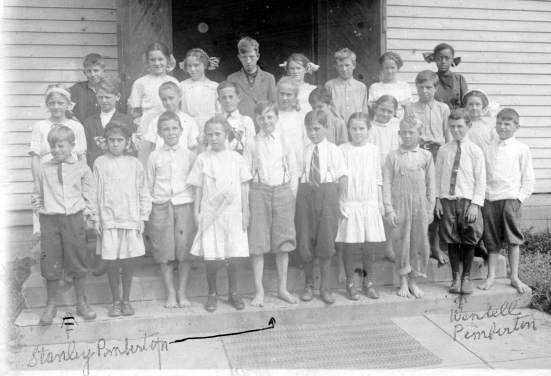

Wendell Pemberton, born 24 July 1906 in Eldora, Iowa, and died 12 January 1987 in Sunnyside, Washington, was the second son of Addison Pemberton, born 27 July 1871 and died 6 January 1945, and his wife Emma Adelle Frey born 25 June 1872 and died 5 January 1961. Wendell was my uncle and I remember him as a witty and fun loving guy who would give you the shirt off his back if you needed it. His profession was farmer and he raised field crops in Sunnyside, Washington for many years. He came west during the Great Depression and found work in the logging camps of northern California. His camp was Camp 10 not too many miles from Klamath Falls and Susanville, California. He was a wonderful story teller and had many fascinating stories to tell. My childhood favorite was the one about how he caught a runaway train engine (no one on board) in the night, crawled all the way around the front of the engine because there was no door into the cab on the side he caught, and brought it back to camp.

died 6 January 1945, and his wife Emma Adelle Frey born 25 June 1872 and died 5 January 1961. Wendell was my uncle and I remember him as a witty and fun loving guy who would give you the shirt off his back if you needed it. His profession was farmer and he raised field crops in Sunnyside, Washington for many years. He came west during the Great Depression and found work in the logging camps of northern California. His camp was Camp 10 not too many miles from Klamath Falls and Susanville, California. He was a wonderful story teller and had many fascinating stories to tell. My childhood favorite was the one about how he caught a runaway train engine (no one on board) in the night, crawled all the way around the front of the engine because there was no door into the cab on the side he caught, and brought it back to camp.

Luckily, he was wise enough to recognize the contribution his true stories could make and he made audio cassette tape recordings of them, which when transcribed filled 260 double spaced typewritten pages.

Notes on Page Numbering

In the following transcription taken from those pages, the page numbers are indicated in brackets like this: [page 46]. During the transcription from audio to typewriter, pages were numbered from 1 through 59 and then from 47 on thus repeating numbers 47 through 59. The numbering rendered in the present edition of his memoirs continues this error so as to make comparisons between the two editions simple. Therefore this section entitled 001 – 051 actually contains 64 pages. The duplicate numbering is handled by using, for example, [page 49] for the first page 49 and [page 49b] for the second one.

His stories begin thus:

M E M O I R S

by

WENDELL J. PEMBERTON

This is the start of my history after all these years, after all the confusion, and now that I have waited until my memory is bad. If I don’t do it now, it will never get done, so I will start out with Addison J. Pemberton, my father, who was born July 27, 1871, in Hartland, Marshall County, Iowa.

He was the second child of Henry Coate Pemberton and Beulah Roberts Jackson. Addison was raised with three brothers; Harmon Elmer, then my father, then George Fox, Francis T. and three sisters — three lovely little girls later — Ruth Elizabeth, Wynema, and Josephine. When you look at the family photo, these four great, big, strapping sons and then these cute little girls that came along later, it is no wonder my father really loved these little girls.

In my early childhood, the only visits we ever made anywhere was to visit Wynema or Ruth, who married the Reverend Brown, and their children. Wynema’s husband was Jarvis Johnson, a great, big, tall, Abe Lincoln of a man–pure gold. He had sons; Max Henry Johnson, the older boy was Byron Johnson, and the younger son, later, was Richard. He had a Thoroughbred stock farm. The farm was at Lynnville, Iowa. During the depression when things were real bad, my father had 720 acres, and he almost gave this to Jarvis, as it was mortgaged. Jarvis Johnson came down and worked that farm for several years when I was a teenager, and we really became acquainted with them and their goodness.

My father’s father, Henry Coate Pemberton, was a designated Quaker minister. There were a great number of Quakers situated in that area. Father’s people were all Quakers from ‘way back, I guess even to the dungeons of King James in England. They told the king that they would serve him with rigor in every detail except in the matter of religious worship and conscience; that that was a free gift from God, and no man had the right to take that from them. 80, they went to prison.

Henry Coate went on a mission to the Osage Indians who lived around the state of Iowa, I think, for eight months. He took a wagon box of seed grain and some white-faced cattle and I think he spent eight months with the Indians to show them that they could [page 2] replace the buffalo and feed their families. There was no paid ministry in those days so Henry Coate supported his family by farming. They always ran cattle. Inasmuch as there was no paid ministry, I don’t know how they were even designated as a minister, but I do know he was a Quaker minister all his life. When I was a teenager, and I remember distinctly, when the Quaker, or Friends, Church decided to have a paid ministry. My father bowed his head and said, to the effect, “In all probability, this may be the end of the good spirit that Quakers have enjoyed for all their existence.” There was never any money. The only letters of Addison’s that I have in my files are when he wrote to his mother and to his father. He was always concerned about how he could rent the place, get the stock, and pay the bills. Addison’s letters, like all boys’ to his mother and dad were priceless because of the great love of these people and their families. They had to share everything. Henry Coate was known as “Henry Do-good” allover that area. He helped many; took them into his home in addition to his own family.

My father, Addison, was a very quiet, tight-mouthed man. He didn’t talk much. He would work all day and only say two or three words. It makes it difficult to write his history when he didn’t talk much. Some, if not most, of the priceless stories I accidentally heard when I overheard him talking to a friend or to relatives at some gathering, for Father never, ever, tooted his own horn — ever, ever, ever. Unless you overheard someone telling these stories, you’d never know. Like the big, life-size, tin negroes off the fence corner — I suppose it was an Aunt Jemima ad. Dad was always fooling with horses and broncs, and rather than ride these broncs, he would tie these big, life-size advertisements in the saddle, and turn those broncs loose. They would go absolutely crazy with fright. They opened their mouths and squalled like all get-out. My mother thought that was terribly, terribly cruel, but it sure saved a lot of broken bones. Those broncs were really sacked out when that tin got to rattling and banging and cracking. They really, really got sacked out. Lots cheaper too.

Now for an example of the kind of people there were in those days: following account I heard accidentally. As Dad was visiting old friends, someone in the group told this story.

Henry Coate, “Henry Do-Good”, and his boys sold a bunch of cattle to be delivered at a place, at a price. When they delivered the cattle at the scales, the old storekeeper and buyer said,

“We’re going to shrink these cattle three percent.

Henry Coate said, “No. The agreement was that the cattle would be at this price at these scales.”

The storekeeper repeated, “We’re going to shrink these cattle three percent.”

Henry said, “No. The agreement was that these cattle would bring this price over these scales here. These cows are really [page 3] shrunk. They have been driven all day in the heat.”

Someone in the store reached over the got the old buyer by the throat, bent him over the counter backwards, and said, “You old so-and-so, you’ve been stealing from this man for years. You know he won’t fight over a dollar but this is once in your life that you are going to keep your agreement exactly as you agreed to,” and with every word he was banging the old buyer’s head on the counter. This was just one instance as to the kind of men there were in those days – men who would go to the defense of the innocent, instantly, with no questions asked.

I never knew my father to violate his code of ethics, not even once in his life. I’ve seen him ground into the dirt more times than I’ve got fingers, by foals, stallions, mules, and I never heard the man curse or take the name of the Lord in vain. You would think he was hard, tough, and maybe even cruel. No. He was quiet, very reserved, extremely honest – an Abe Lincoln. Remember how Abe Lincoln returned the pennies on the long walk? Well, when my dad was a little barefoot tyke, he walked through the hot sun to the neighbors and returned a walnut. They didn’t have walnuts and when Mother Pemberton [Buelah Roberts Jackson] checked under the bed, she found this walnut. She asked Addison about it.

“Did they give it to you?”

He said, “No.” So he walked back, returned it, and told them he was sorry.

My dad was sworn at and swindled more times than I’ve got fingers and toes. On the ranch, his hogs, his cattle, and sheep were stolen. We always had someone on his places. Every time he got a chance, he would set up some young man in business. The ones who had anything on the ball all made good, and those who were the unfortunate type, of course, they never did and he couldn’t help them. I remember one family he had on the place for years and years. Every fall when they went to settle up, the woman would claim she had lost the cream receipts, and my father would sit there. “Well, what do you think? What do you think is right?” They would haggle around and around, and he would accept whatever the woman said. I thought, “What on earth! How can my father sit there and take that, year after year?” But he did. His philosophy was that the Lord had a way of taking care of those kinds of things.

Addison was educated in a little rural school and graduated from the little Quaker Academy at Hartland, Iowa, that’s the Friends Quaker Academy. Most of his friends lived northeast of Des Moines a little ways, around Iowa Falls, Eldora, and Marshalltown. Hartland is close there some place.

As you will note in his letters to Emma before they were married, Addison was always buying and selling cattle. My father was a cattleman from the ground up. He just couldn’t pass up a calf in a pasture without wondering if it might just possibly be for sale. His total philosophy of economics was to keep a little bunch of stuff growing into money at all times. You could be sure [page 4] of course, this meant livestock; corn, hogs, sheep and cattle, you name it, and you can be sure this was his father’s philosophy also. The first year that Dad farmed was in partnership with his beloved Uncle Jim Jackson, known as J. C. Jackson, (they always called him Uncle Jim). Jim was father’s mother’s brother. Dad loved this good man. My younger brother, JC, was never given a name; he was given the initials out of love and respect to this great man that Dad had in partnership, and in their first year farming and feeding out cattle, they netted $10,000. In those days, that was really something.

When Dad went on his own, his first place. was called the Ball Farm. We have a photograph of the emblem, or coat of arms, up on the end of that big barn. I think he bought this in 1902 where his first son, Stanley, was born. Then he moved to what is known as the Cross Place where I was born, Wendell J. I was not named Wendell J. I was named Wendell but I, like my father when he was about twenty years old, added the initial J. Unbeknown to me of this, I did the same thing at about the same age. Four years later, about 1907 or ’08, he went down into southern Iowa, 65 miles southeast of Des Moines, and a hundred mile straight east of Omaha, and bought a place on what is known as Mid River. There is the Des Moines River, the Mid River, and west of that is the Nodway, and I do not know the number of acres. My mind says it was always called the 92 acres, but I don’t think there is any way it could have been that small. It could have been 292. Anyway, that was my childhood. About 1907 when I was one year old, they built a big, new, two-story, white house on top of a hill. Overlooking all the river and timber country below us, the land laid to the south of us and to the west of us and to the east of the house and started up again. It was pretty good pasture but the sprouts had grownup to four or five inches in diameter by that time. It was 12 miles south of Stewart, maybe more; anyway, it was 12 miles to Greenfield; about three miles north and nine miles east of Greenfield to get into this place. The schools were all two miles apart in those days, originally laid out and surveyed. Our school was called the Prior Schoolhouse where we turned in toward our place, one-half mile, opened the gate, drove around the ridge a full wide circle and came into this big, white house.

I never knew why my father left all his people and all his community and came to this country and bought this place unless it was because he was raised on the Iowa River and his mother was the fisherman of all fishermen. Anyway, that is what he did. My mother was quite the lady. She taught school for years before she was married, and she was always–I don’t know how to say it–she was a lovely woman, she loved people, but she wanted to be educated and wanted to always be in with people in society. This may have bothered my dad, I don’t know. Anyway, he bought this place, and this was our home during all of our growing-up years. This is where we were raised. This is where we learned the great [page 5] lessons of life in our early childhood.

I will now go back to 1907 and put in what I can first remember. There is no way I can make this history chronologically correct, and I will try to mark my notes off as I put them on the tape. Anyway, on the first place Dad bought on the river, over on the west side of the place there was a deep ravine that ran clear through it, and back over there was an old original house–really old–down in the bottom. It had timber around it. The only thing that I can remember–now this was before we built the house and I couldn’t have been over a year-and-a-half old, all I can remember is where the back door was where you came in,. the old, black, cast-iron cook stove, and the chimney in that corner where I sat and played with Old Tom, the tomcat, my pet. Try as I might, I cannot remember anything about the house. I can see the stove and the kitchen table. I don’t remember where my bed was, but I can remember that corner where I spent so much time. My mother always let me have this big old beautiful tomcat to play with.

The next memory was after we built the new house–I don’t remember a thing about building that house, or any of the construction at all; not one single thing, but after it was built, they extended a wagon out, took four head of horses and loaded a red grainery that was by the old house. They took it down, forded the creek, and the creek was up. I was up on the front seat with Dad and another man. To see those four horses go down into that water, lunging and plunging, scared me the worst I have ever been in my life. I can still feel the fear. I was just sure we were going to get thrown in that water.

The other things that really stick in my mind are the terrible fears that I had. There were timber wolves there in the early days, and lots of them. They were always killing our sheep. They were always killing the pigs. My father never owned a gun after us boys were born. He’d had a gun all his life. He was always telling us what a fabulous shot he was with his old 10-gauge, but he wouldn’t have a gun in the house after us boys were born. Guess why! We sat in our big front room window and watched two wolves come up one day, across on the other hill. The old sow had piglets over there. These two wolves came by and one wolf would go and get the old sow to chase him and then the other one would get a piglet. The two of them would eat the pig. Then they came back and repeated that about three times and this big, 01′, lean, red sow finally caught that wolf going downhill and broke his hind leg. The last we saw he was going ‘cross country with his hind leg swinging completely loose. Dad went out to harness a horse and went over there with a pitchfork but of course when he got there, it was allover.

I always went to bed at night to the music of the bawling hounds–or training hounds. They would chase wolves across that country all night long. Somewhere, up the river five or six miles; down the river five or six miles, or right past our house, here would come these hounds, and it never ended in all those [page 6] years. I remember Christmas. You could bet my mother always had some kind of a Christmas. There were no evergreens, of course, so we’d borrow from the neighbor a limb or two off their trees so we could have a Christmas tree, or a sample of a Christmas tree, in our home.

One thing I remember very distinctly. I was fooling around with matches and Mother had her bread, always, in the frontroom–I guess the kitchen stove must have been out–and she had newspapers up over this great big rising pan of bread. I was fooling around with this match, just kinda seeing what I could do, and I lit the corner of it and put it out; I lit it again but I must have been too slow. It flared up and really was going! I ran out into the other room and asked if they smelled smoke. My Dad caught on right quick and Man, did I catch it!

Oh yes, there was another. Dad’s younger brother, Frank, was a football player–a real young boy at that time–great big guy. This old red shop they pulled up from the old house and forded the creek with, stood out by the house, and up in there opposite the workbench was a great big shelf. I could step from the workbench and somehow crawl up on this old shelf. There was an old horse blanket up there and Old Torn was up there. I was lying up there petting Old Torn, and Dad’s brother carne in to work at the bench. He had the biggest straw hat I had ever seen in all my life. I had to have something to do so I reached Old Torn out into the air, held him over this big straw hat, and let go. Of course the cat went crazy, scratching to get his balance, pulled off the straw hat, and scratched Frank’s head like you can’t believe. I got the hardest spanking I ever got in all my life!

The horse barn was in back of the big white house, about 50 yards, I guess. It had a buggy shed on the side of it where we kept the buggies. For years, there was a five-gallon can of linseed oil there left from building the house. Guess what! My curious mind always got me into trouble. I took a hatchet and cut holes in that can to see what was in it. Of course the linseed oil ran out onto the ground. When I got cornered, I told my dad, “Well, I just got anxiouser and anxiouser and anxiouser to know what was in that five-gallon can.

Another thing that sticks in my mind as plain as if it were yesterday: my brother slept on a cot and I actually slept in a crib until I was a pretty big kid–maybe three or four years old–I don’t know. Anyway, those hounds one night brought a big old timber wolf in from the west, I think right down through the buildings and backed him up against the side of this big, new, white house, if you can believe it. We both got out and looked out the window, right down on this wolf, and I was so petrified with fear that I never got to see the wolf. The old wolf sat there until he got his breath and then he’d make a lunge at the hounds, and they’d melt like water. When he got his breath again, he dove into them and they opened up like a wave of water and away they went again! And I never saw the wolf!

[page 7] Another highlight of my childhood was what was called the Old Settler’s Reunion. On the river, a mile west of us and then a mile down river — if we went out the back way, was what was called Arbor Hill or Fort Union. They freighted supplies into there in the early days and that store stayed there for years, 14 miles from Stewart on the north and 12 miles from Greenfield on the south and west. I can still remember the white peppermint candy in the store. If I had a penny, I could buy about ten of those white peppermints — if I ever got the occasion. This Arbor Hill had a curve in the river and a great big flat green pasture where the Old Settlers” Reunion was held every year for years and years. They had the complete carnival and the whole ball of wax — from cotton candy to you-name-it. This was the highlight of my childhood. See the picture of us four kids, Stanley and I and two neighbor boys, Dale and Lloyd Wambo, who joined our farm from the south, on this white burro that Dad bought. He bought two burros when they were just cute little ones and they grew up — one to be an ugly, ugly brown burro but the white one was real cute. She was white and tipped in black, and she became the “pet of pets”. She’d stay at the dining room window and we’d feed her bread crusts and prunes, and she would stand there and eat prunes and spit the seeds out, if you can believe it. Through all those years, we enjoyed that pet burro. We called her “Peggy” and we rode her everywhere. We took her to school, and the kids would sit under her and eat lunch. I never knew her to step on anybody.

In all this history, you must remember that my brother Stanley was four years older than I, and we were always together except those terrible times when he went with Dad to do this or do that, and oh! how I hated these words, “You’re too little. You can’t go.”

Stanley went to Chicago, with Dad with a trainload of cattle more than once, and he went to the State Fair with him several times. I never got to go to a State Fair!

We did have an accident one time with this wonderful burro, Peggy. Dad was walking behind her and had spent all day on foot and was tired so he grabbed her tail to have her help him along. Hey! She didn’t like that and she pitched both us boys on our heads on that old hard dirt road, and I can still remember how that hurt. I think that was the only time she ever threw us off.

Now, about my mother. She was one of those 95-pound wonders of the world. She taught school for years before she was married, and had fabulous-ability. In those days, there was always a bully around the country–I suppose there still is. She was aware of this bully at this school, who had run several teachers off. This 95-po.und wonder went in the first day, sat up there, folded her arms, and laid down the rules that “will be followed”. She called this big boy by name, and she says, “You know, I have a splendid horse that I ride to school, and I want him taken care of and [page 8] taken care of right. Now, I know that you have the ability and the know-how, and I would be very pleased if you would care for my horse like you know how to care for it.”

That boy never gave her one bit of trouble. I’ll tell you, when my mother stretched her 95 pounds up to full height and looked you in the eye … well, I never knew anybody that she couldn’t melt down. Do you know what she did when she first went down to that country? She was on a horse–an excellent, excellent horsewoman. Dad had two Morgan horses. One was a dapple grey, high-strung and flighty, always in trouble, and the other was old polly. Polly was the gentlest Morgan horse–beautiful and trustworthy–that ever lived. We were raised on that horse. I can remember the horrible fear when I was about a year-and-a-half old on up, of being in the saddle with my mother when she’d coax that horse down a steep, rocky bank, across the river, and up a steep bank on the other side, plunging and lunging. I was just petrified with fright, but she never showed fear. She loved the woods.

Always in the spring, she’d take me on that horse and go through the timber, always singing and pointing out every kind of flower that grew native to that Iowa timbered country. I can’t even name them now–the Bloodroot, Honeysuckle, and a whole bunch of others. She knew them all. This was her life. And, oh! how she loved people. Anyway, she made acquaintance with that whole area and gathered up all of the young kids in that area and started a Sunday School. Those kids grew up and paired off and the names always went together like Ray and Letha, Rex and Gurtie, and so forth and so on, and they married and had their families and I never knew of a divorce in all of their descendants. I am sure there were, but I don’t know of it.

From our house, we couldn’t actually see the river because north of it, there was a high hill, but the road north of us, the culverts washed out and were never replaced. There was a high, steel, plank river bridge with metal structures that were real high above the water. When we went to Stewart, we could go through our place and cross this bridge and come back that way, but for years, to go out north and west of our place, the road was out, and when Dad was out in the country, to the north or east and was late, mother would always hang a light in the window. If he was to come from the south or the west, she put the light in the south window, but Mother always put that light in the window.

I don’t know how old I was when we got our first sheep and, here again, to go get the sheep would have been quite a thrill. I knew what sheep were but we didn’t have any. Well, I couldn’t go. I was too little. Anyway, they didn’t come home, and it got dark. Hours passed. That light had been in the window for hours. Mother would shine that light up to the reflector, and I could see the anxiety on her face. She knew something was wrong. At almost midnight, we heard the men coming with the sheep. They had had to make the sheep cross the high river bridge, and they almost went [page 9] crazy trying to get them across, because of their fear. They would tie one and lead it and try to get the others to follow. Dad had a big tough buggy whip that he had worn down and just had a stub in his hand, about three feet long. When he came into the house, in the light, he had this whip in his hand, this stub. It had a tuft of white wool stuck in it. I remember I reached out — I was small enough — and I took that tuft of wool and felt of it and smelled of it. I had never had ahold of wool before, and it was quite a thrill.

It was the beginning of a fabulous, fabulous experience in our lives because for the next few years, we always had sheep, and the thrill of raising those crops of lambs, year after year, and seeing them romp and run and play, was really something. By the side of the big white house was an old cave, a dirt-covered old cellar that was sort of poorly built and partly caved in. The lambs would play “king of the castle” on that thing by the hour, day after day.

I remember we had a pair of lambs that we had broke to the harness and put on our little farm wagon. Their names were Buck and Barry. I have the pictures, and the thrill we had all those years was really something.

The wolves were horrible. They were always into the sheep, and this fabulous little mother of mine–I don’t know how old I was–maybe three or four, and the wolves had hit the lambs when they went down to the river to drink. They had run them over the bank, in a bayou, where there was a deposit of about three or four feet of slimy, oozy, mud. There must have been 6 or 8 young ewes, just ready to lamb, and my mother went out in that mud, waist deep, and helped work those lambs out. It was a terrible, heavy job and several of those young mothers bore-twins under that water and in that mud. We laid them out on the bank and wiped them off the best we could and I think they all lived. I can still remember the agony of trying to get them to the house, about a half-mile away, in the worst down pouring cloudburst you ever saw, trying to coax these mothers along. We’d put the lambs down in front of them, then we’d pick them up and go another few feet, but the mothers kept racing back to where the lambs had been born. Then we had to go back and start allover again. I thought it would never, never end. In the years before I went to school, I can definitely remember three crops of lambs.

It was quite an ordeal when my brother, four years older, left me and went to school, and I was left alone. I got into all kinds of trouble. I just couldn’t find enough things to do by myself and, you might know, I did a lot of things that got me into trouble. I sat under the lawn mower, which was up against the side of the house, and one of those blades came down on the middle of my forehead and split it wide open. My mother just about went crazy. Another thing we always had to fight was the wolves and dogs. Dogs love to kill sheep. We had a big, beautiful, black-faced buck we called “Old Joe”. We had him about three [page 10] years. I don’t know whether you know it or not, but when the rams are turned in with the ewes in the fall, the rams fight like the wild goats and Bighorn Sheep fight. They jump 15 or 20 feet and hit in midair and when their heads hit, you can hear it for two miles. This is what we witnessed every year, and many times during the season. Anyway, this Old Joe could take on any dog I have ever seen, or two dogs. I’ve seen him hit a dog and bowl him for 50 feet, end over end. We had Old Joe down to Grant Bunche’s place–that was about 1 mile south and a mile east. Grant Bunche worked with my father for many, many years. They always had him on the place somewhere, somehow, doing something, to try to help them out. So, anyway, Old Joe got killed. We went out to find him on the hillside. There were little skiffs of snow on the ground, and there were three wolves; one with huge tracks, one with medium-sized tracks, and then the female. They had covered that whole hillside and- had split him to ribbons before they finally got him–because there were three of them! You could see the marks where he had hit those wolves and rolled them in the snow for 50 feet, where he had slid 15 or 20 feet, and where the other wolves had come in from the side. He had to turn around, so while he was getting that one, another wolf would attack. They finally killed Old Joe.

It was a really sad occasion. We’d had that old man for years, and we loved him. He had never hurt one of us, however he did hit a stranger a time or two. He never did tackle us boys because we were with him all the time and I guess he just naturally respected us. Probably the reason I remember this period of my life so vividly is because Stanley was in school and I was alone.

Dad would never take care of his own livestock doctoring. He always had Steve Jackson, the neighbor, help him. It was always like a circus. Dad never got his stock taken care of when he should have — somehow he never got around to it and they got to be huge animals when they had to be docked, castrated, and so forth. We had a horse barn with some slats out of the back stall. One day when I was up in the haymow, a great, big, hog came through this open place in the manger, went down along the manger and picked-up the shelled corn under the horses’ boxes. Now, I had seen the men take a piece of hay wire and make a snare to snare the snouts and mouths of a hog so they could put rings in–so they couldn’t root out the pasture.

I’ll be darned, wouldn’t you know it, I made me a snare out of hay wire, fastened it to the rafter, dropped the loop down and caught this big ol’ red hog by the nose and jerked up on it. Holy Mackerel! That hog started to squeal and wham his head back and forth against the planks of the manger, and shook the dust out of the rafters of the barn. I was so petrified! To this day, I have no idea how I got that hog loose before Dad got home. I must have, somehow, because I don’t remember Dad learning anything about it.

[page 11] Another time when I was up in that same haymow–I don’t know if I had seen a circus–but I stuck a plank out there and was playing bear or monkey or something on this board. I went out there 15 times and turned around just before it tipped over but this time, for some strange reason, I was out a few inches too far, and that board flipped up and shot me down on that old, hard ground in front of that horse barn, on my forehead. I think my mother saw it from the window. I think she was just coming out the door to warn me when it happened. I still remember I thinking I would never ever get air back into my lungs again. My mother sat there in the dirt and rocked back and forth with me — it seemed like forever. You can bet she was really doing some praying but, of course, eventually I got my breath.

I know you can’t believe, that a boy that young could take those sheep out on the big ridge by the side of the house and hold them there by the hour and by the day and keep them out of the corn. Now, that place was fenced with hog fence clear around the entire place, but it was not cross-fenced inside, and for years, it seems, I took those sheep out on that hill and kept them out of the corn. Mother called me Little David. She’d read me the story of David out of the Bible and, you know, that really pleased me. So I was known as “Little David”. How many years that was before I went to school, I don’t remember.

One time when I was herding the sheep, I got so lonesome I just couldn’t stand it, so I went down to the school. They were having school; the door was shut; they were in class, of course. I went up to the side of the door and took a short board and went down the siding. Brrrrrrr. Then I’d run and hide. The teacher came out, looked around, didn’t see anything, so she went back in. Then I’d go up and run this board down the siding, Brrrrrrr. She’d come out again and look all around. I thought that was pretty cute. The third time, I was just ready to raise the board when she reached out and got me by the arm. She invited me to come in. She sat me down and started to talk to me about how I was disturbing the whole school — that she couldn’t hold class and that it wasn’t real good — that she was so sorry to think I would do that. Then I had to tell her something. I said, “I don’t know what it is, but there are certain times when my eyes water, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it. They just water and I can’t help it.”

I neglected to mention my birth on the Cross place. I that on this Cross place was a great big old stone house. know, my birthday is the 24th of July, and Dad had several men around the ranch. My little 95 pound mother had a horrible delivery. I don’t know how many hours it was, but it was a long, long, long siege. When the sun came out in the afternoon, the heat was unbearable (over a hundred degrees, I think) and she used to tell how the men ripped the plank off the corral fence, and stood the planks up on end against the west side of the house so the house and its windows were shaded. She told many, many times [page 12] how grateful she was for what those good men did.

Mother was a fabulous cook. She loved people and people loved her. We never had a hired man in our lives that didn’t love and respect my mother because of her goodness and her fabulous cooking.

Another thing that happened when I was just a little tyke — we had the workhorses in the yard, old Polly and Dolly and a bunch of bigger, rougher horses. My brother was shelling ear corn out into little piles on the ground for his special horses, Old Polly and Dolly, and of course, Peggy, the burro. Of course the other horses were trying to get up there to get their noses in there for a bite, and Stanley says to me, “Get them outta here!” So, I took a little stick, about two feet long, put it back over my head, and rushed at this horse which had just been shod with iron shoes — it may have been Old Polly, I don’t know — but it laid back its ears and kicked me in the chest with both feet with those shod feet. I remember it as plain as if it were yesterday. The telephone pole was in the yard, and it came down past me and then went right back up again. The insulators on that telephone pole came down past me and then went right back up again; I was kicked that high into the air. I don’t remember any pain at the time of impact, at all. Don’t remember a thing. When I opened my eyes I saw my Dad — he had been shaving and had jumped into the air off that high front porch — in the air with one side of his face shaved and one side not shaved. That’s the last I remembered. When I “came to” I was lying on the old couch in the front room, and then, Man! the pain began to cut loose!

My parents had been on the phone. Mother’s sister, Mary, who lived in Greenfield, had married a doctor, and he was a good doctor. He had a set of running horses. He had the harness hung up over them, like fire horses, so he could go out there, pull a rope, and the harness would drop onto them where he could just buckle the harness. The buggy tongue was right there, dropped down between the horses, and he could get out of there fast. I don’t know how many miles a running horse makes–maybe 20 miles an hour, but he didn’t come and he didn’t come and Dad called back. Old Doc says, “Well, I haven’t had my supper yet.”

I heard my father say, “Well now, we don’t know if this boy is going to make it or not,” and he hung up the receiver. I think the doctor was out there in something like eighteen minutes.

Incidently, before I forget, Father’s little beautiful sister, Josalee, married a man by the name of Ledas Williams and died at her first childbirth. This was one of the saddest things for my Dad. He could never bear to talk about this terrible, terrible tragedy.

Here is another thing I want to mention: The only good horse Dad ever owned, he brought to that country, a fabulously high-spirited riding horse by the name of Old Robbie. A hired man came in one day with a four-horse team and tied them to a hog tree. They panicked, pulled back, and roared down through the [page 13] orchard where they piled up, broke Robbie’s neck and killed him.

Down at the river there was a layer of limestone about nine or ten inches thick, and where it broke off and the water came over that, it would always dig out a hole, causing a whirlpool that went about 3/4 of a turn and then went out at about a right-angle to where the water came downriver. Because of this whirlpool, a six to eight or nine-foot hole was gouged out there. You could touch toes on the bottom and not make your hands stand out the top — it was that deep. Anyway, that was the joy of our lives while we lived on that place. Even years later, after we had worked around the country, that 0l’ Swimmin’ Hole at Teakettle Falls was our pride and joy. Our friends from town would come out there time and time again to go swimming at Teakettle. We could climb up into the willow tree, that hung out over it and bale out of the tree. One time, I pulled a horse and buggy up there, dove off the wheel and hit in six inches of water. Darned broke my neck. Did break my left arm, or cracked it. Anyway, I carried it in a sling for six weeks — never went to a doctor with it. It was definitely cracked though. A kid’s bones will crack like a green twig and, like I said, it was six full weeks before I could use that arm like I should.

My father was not a mechanic. He hardly even had any tools around the place. His tools were literally a hammer and a stone. He wasn’t a good fence builder. He built fence when he had to, but he always had hired men. Would you believe it? There was nearly always stock in my mother’s yard? We had a great big lawnmower but I guess Dad figured the sheep could do a much better and cheaper job. The sheep were always in the yard. They kept it down nice. Know what? When Dad moved off-that place and had a renter on there, the first thing they did was fence the area. We had a garden fenced south of the yard where Mother always had a fabulous garden, but Dad just didn’t build fences like other men did.

One thing I forgot to mention about these sheep that I used to take over on the hill. There was a creek that ran back of the garden, south of the house. A ravine ran down through there, quite a steep one. The sheep would come off the hill, go down the slope through the timber to the creek, then come up east of the house and go into the pen where we always penned them up at night. One day, I started the sheep home and then I took a shortcut across the back of the barn past the old pump down the top end of this draw, and then into the house. My brother and I were sitting on the porch watching the sheep come up. Some big lambs came straggling along, long after the others had come up. They’d go always and then lie down; go a few feet and lie down. We thought, “Hey, what in the . . . and here another one carne o~t of the brush, in worse shape than the first one. We ran down there. There wasn’t a drop of blood on them anywhere.

“Hey, what in the . . . and here another one came out of the brush, in worse shape than the first one. We ran down there. [page 14] There wasn’t a drop of blood on them anywhere. They kept lifting their heads, like they couldn’t get their breath. We went down there, and there were two or three dead ones. Three or four or five of them had had their throats cut by the wolves. They had cut the jugular vein and sucked the blood out of that wool so clean that you couldn’t see blood on the wool, if you can believe it. Wolves are artists at killing stock and cutting the jugular veins.

Another time when we came home — here again, the folks had to go clear around the ridge, about a half-mile and make the big loop and back down to the barn — but us kids, we’d get out, shut the gate, and run down through the timber, past the garden, and into the house. We’d been gone for a few days days. When we came back, we went past the horse barn, and just happened to look into the manure door window, and there, sprawled out in about half of the horse barn was about 40 big old hounds. My brother gave me the high sign and I peeked in there. He said, “You go shut one door, and I’ll shut the other.”

We ran around the barn two different ways and shut the doors, got those hounds locked up in there, but then what? We hated the things because of their noise and ruckus and the sleep we had lost, but we didn’t know what to do with them. Finally, we just had to let them go. They got pretty ugly. They’d bellow and bark and raise Cain in there.

Another time when we had been away for several days, to a fair or something, we came home and us boys unlocked the house and went in. My brother was ‘way ahead of me because he could run faster, and he came back as white as a sheet. He still says there was someone in that house. Because the house was on a high hill in the corner of four sections where there was no road used, it was a really isolated, back-in-the-woods affair.

Another time when I was very young, a man came walking, a great big man with a long overcoat. He knocked on the door and said he was hungry and had to have something to eat. Dad brought him in, set him down, and Mother fixed him a nice meal. He didn’t take his coat off, and he watched Dad all the time. When he sat back in the chair, his coat opened up. He was wearing two guns. We never had any idea who he was or what the deal was, but he really made Dad wonder what in the world was going on.

I don’t think I have mentioned this Fort Union that we always talked about–where we went to get groceries when we didn’t want to go the 14 miles to town. There was a mill just below the store on the river, with a millrace and a great big overshot waterwheel. Mother always raised chickens and it was quite a thrill to go with Mother in the buggy to take the corn down to this mill and grind the corn for the mother hens and the chickens–she always had these little chickens coming on in the spring. I have never forgotten the thrill of watching the mechanics of that mill and the turn of that big old stone with its big old wooden homemade cogs like you see in pictures of antiques. It was really [page 15] something. Above the mill, north of our west place which we bought later, originally there had been quite a dam in there — quite a dam. They had bored holes in the rocks. It had a limestone rock bottom. They had bored holes in these rocks and had pinned 8′ x 8’ timbers across there, and made the aisle for these timbers and filled the center with big chunks of rock to make adam to raise the water to this race that turned the mill. In my later years, of course the mill was all gone and defunct. The dam had been ripped out by high water, but it always intrigued me to go over there and when the water was real low, you could see where these irons had gone down into the limestone to anchor the dam. I used to think how wonderful it could be if we could get folks together to rebuild that dam and have a place to swim above it.

Another horrible experience I had when I was a very small boy — Dad had built a big stallion barn across the road, east of the house. It was fenced on both sides but it was never used because the culverts had washed out and were never replaced. Anyway, Dad was in this stallion barn, nailing up some feed bunks or something. The half-door was closed. An old sow lay outside the door, about 3 feet, with about twelve of the cutest little, speckled black and white and red pigs you ever saw in all your life. They were just darling–just out of this world! I opened that door and slipped out there and got one of those little pigs up in my arms. Of course it squealed, and when I turned to go back into the barn, the old sow looked at me like a roaring lion. She bumped the door shut–with me on the outside! Here was that old sow about twelve inches from my throat with her mouth wide open, roaring like lion. Hey! I could not move; I was so totally paralyzed. Dad came down from the rafters ·with a hammer and stuck a hammer in that old sow’s head and she was out cold for about three minutes. I remember that one as well as if it were yesterday.

I don’t know when Dad got into the land business in a big way. I assume it must have been after we bought the 160 acres in 1913, on the northwest edge of Greenfield, known as the Duncan place. This was where J. C., the third son, was born. This was a well-improved farm, big corn crib, large barn, grainery, and would you believe, running water and electricity for the first time in our lives? That was really something!

In 1913, he bought the Willys Knight, the Overland, with the old sleeve valves and that old cone clutch. Every time he let the clutch out with the motor revved up, he’d break another axle and have go to have it fixed again. That car would not stop even if Dad yelled so you could hear it in the next county — if you don’t believe it, ask Emma. After he’d had the car for about a year, they came out to the big gates of the house and Dad said, “Now, Emma, there’s no reason why you can’t drive this car through the gate.” So she said OK and slid over. He showed her the gears to put it in, how to put the clutch down and let it out REAL slow. [page 16] And so, she went through the gate, yelling, “Addison! Addison! How do I stop it?”

Of course, Dad was already yelling WHOA, but that car chugged, chugged, and she ran into a plum thicket, ten feet high, and mowed down a 50-foot swath through that plum thicket before that old car chugged itself down and drew its last breath.

As you might know, my mother said, “Now, listen, Addison, these boys are getting to the age where I am not going to see them grow up out here in the sticks. They must have better schools and church.” So, in 1916, he bought the house in town.

Dad was gone by the day, the week, and the month–over and over. He had land in Wisconsin, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Colorado, you name it. Some of it I never saw — didn’t even know it existed. Do you know what my mother did when her boys were so much without Dad? She gave us the entire upstairs bedroom, and stanley shelved the whole side to store stuff on. Then he took out the upstairs window, and we put planks and lumber up to that window by a rope and pulley, and built a big workbench. She gave us a full set of wood tools so we could make anything you could imagine. We had shavings on that floor, 8″ deep, for years to come. How blessed we were for that experience. That was mother! We would build birdhouses, stools, chairs, bicycle carrier boxes that would haul pigeons thirteen miles — and they lived too! If they got out they were probably so shook up they couldn’t fly anyway!

Anyway, somewhere about this time, my dad bought 240 acres west of the home east place. The east home place was on the road in front of it and two miles west. It was three or three and a-half miles if you went around the road; If you walked across from place to place, it was only about a mile. He always had a renter on the place. There was a man by the name of Walt Davis who was there for years and years and years.

After the crash of 1918/19, this 240 became the family home. The house in town we lived in for probably four or five years, and always ran from that property, every summer, out to work on these farms during harvest. Dad also bought forty acres about six miles south of the original home place, and a mile south of that, he bought a 160 with no bUildings on it. The forty had an old house and a barn where we could get in out of the cold and sleep at night. We worked on this 160. We had cattle on there every year, and grain. It was quite an experience, traveling that distance from the home place — we didn’t go from the 240 down there, but we traveled from the home place with this old man, Grant Bunche, who was on the original home place after we moved to town.

Trip after trip, by team and wagon. We’d take our lunch and go to work on this 160. We did that for several years–a horrible waste of time, but that’s what we did. It had rattlesnakes on it like you couldn’t believe! We had to watch out for them all the time.

During these years when Dad had land allover the country, he [page 17] was gone, gone, gone. Mother waited and waited, and one night she was sitting on the porch when suddenly she ran down the walk and threw her arms around this great big man. Guess what! It wasn’t Dad! He was a real fine person — just a really swell man — and he laughed and laughed, which completely put Mother at ease, and she didn’t have a bad time over that at all.

[page 18] CHAPTER (Tape) II

I need to backtrack a little now, back to the winter of 1911/12, one of the most savage of winters and what probably set the cold record in the state of Iowa up to that time. I have in my hand a letter that cousin Howard Frey’s mother wrote to my mother’s sister in Greenfield, Iowa, Mrs. Mary Babcock. She says:

“The weather situation .is becoming very alarming here. Last Sunday it was 36 degrees below zero. Fuel is very low. Freight trains are stalled, and sixteen of the mines have shut down. The railroads refuse to handle stock shipments. A car of cattle came through Clarion and were partly frozen. We got part of our hogs off before Christmas but they won’t take the rest, and we haven’t a kernel of corn but what we can buy at fifty cents per bushel, and can buy only a limited amount at that. We have coal to last for about ten days. I don’t know whether we will get any more, and when this is gone, we’re out.

“Apples froze in transit from the depot to the grocery store–two or three blocks. The merchants can’t get groceries; sugar, buckwheat, or beans.

“I made a bed down on the floor by the stove for two nights; the bedroom is so cold. It was so hard on the floor that my flesh is sore, but by sleeping in our heavy, flannel underwear, we managed to not suffer too much.

“When I hear people talk about ‘the good old pioneer days’, I think they should look around. There’s plenty of it here. People have to take their children to school. Howard gets a ride part of the way. He hasn’t missed a day. He froze his face one morning. “This is the worst winter recorded since 1864. I know it beats anything I have ever heard of.

“There is a funeral party stranded in Wyoming, trying to get here.”

Howard adds: “This is the winter that Mother Frey, my mother’s mother died in Greenfield. It seems that from childhood memories, I remember it was a hard one. I think that is the winter of record cold for Iowa. It did get down to 47 below, west of us, here.”

Then I wrote on the bottom of this letter, “I am Wendell J. Pemberton, your cousin. Yes, how well I remember the winter [page 19] of 1911/12!”

It was 40 below, and a three to four day blizzard with high winds came up. Huge snow drifts everywhere. The sun broke out on a crystal bright, clear morning after the storm. The sun on those frost crystals at 40 below, looked like millions of diamonds. It was ust out of this world. Our animals, the hogs and sheep, were all in the barns and the big shed in back of the horse barn. The wind was from the northwest.

“We sat in our parlor and saw three big timber wolves come up out of the timber, jump over the high fence into the front lawn, about 30 feet away. They were so thin they looked to be about eight inches wide. They were continually raising their heads and sniffing, catching the scent of our stock in the barn. They were so gaunt and thin that they were totally fearless. I can picture them as clear as if it were yesterday. My father would never own a gun since we boys were born even though he told us many stories about his old 10-gauge.

He took a pitchfork and tracked the wolves around the buildings, south and then back northwest of the buildings, about a quarter of a mile from the house. They had gotten down into a ditch where there had been a little waterfall, and dug out a deep hole. They had crawled in there and were covered with two to three feet of snow. When the storm broke, they crawled out, circled around to the south, started down to the river, but when they smelled our animals, they immediately turned and came straight towards the house.

I forgot to mention the thunder of the ice on the river, at 40 below. You could hear it for five or ten miles when it let go, as many as two to three times an hour. It is like a chain reaction when it lets loose in one spot, and then travels for miles up or down the river. Then it is quiet, freezes, builds up a terrible pressure again, and then Boom-Boom-Boomtety-BooMl Isn’t is something to have a belief and leaders who have counseled us for years and years, since 1936, to keep at least a year’s supply of (staples at least) everything you need to use and preferably two year’s — fuel, clothing, everything.

We were snowed in here one year when nothing went down the roads — not even a snowplow. What a thrill it was!· We sat here without one thing to worry about.

Now I need to go back to 1913. We had moved from the place out on the river, the Duncan Farm on the edge of Greenfield. Now I don’t know when we moved. usually, the terms of lease-purchase were always in March, but I have my report card in hand, from 1913, and I had started in the [page 20] middle of the year. How well I remember that one! Here is what happened.

I had gone to the country school a year or maybe a year-and-a-half. Anyway, a great, big man I had never seen before, wearing a blue serge suit, walked into the classroom, and had the teacher call me up in front of that group. He handed me a book and told me to read. Well! I was so scared I couldn’t even see the book — I just gulped and swallowed. He said to the teacher, “Put this boy back a grade,” and he turned and walked out of the room.

Can you believe the ignorance of that? I have my report card in hand. I remember my teacher very well; she was a good teacher. I got “G’s” in everything except in Drawing and Deportment. I got “F’s” in those. I never got a high grade in deportment. Guess I had too much fun!

never got a high grade in deportment. Guess I had too much fun!

I have my report card from Grade II, and it is all “G’s” and “E’s” straight across the page. Even my Deportment is good except for one which is “Fair”. So, maybe it was a good thing I did get set back. I’ll never know, but I’ll always remember the disappointment and horrible feeling of that cruel experience. However, I guess it was a good experience, at that.

The three years that we lived on this Duncan Place, so many things happened that were so important in my life at that time. I was seven years old in ’13, and had to totally change friends in a new school. I explained someplace (or did I?) that that place had running water and electricity, for the first time in our lives. It was on the edge of town, but between town and our place, there was a fenced-in park of about four acres with every kind of beautiful tree that grew in that area — even evergreens. Adjoining this a place was a little apple orchard, a big grazing area, a big barn, and a big beautiful doublewide corn crib. The house was small but quite comfortable. Father had apparently started wheeling and dealing in land by this time because he was gone quite a bit of the time.

One of the first agonizing things I remember was the big hogs we kept next to the corn. They had raised up the fence, the big old sows, and gone under and into the corn. Hey! My brother and I drove stakes into that fence by the hundreds. I mean, stakes 2-3 inches through and three feet long. About 40 of those old sows would get their noses on that fence and they could lift tons and tons. They kept ripping it out and ripping it out! Here we were, two kids. I was seven and stanley eleven or twelve; Dad was gone. So we finally braided a barbed wire and made a braided cable, and put on the ground. We stapled and nailed it into those huge stakes. We drove the stakes ‘way down with a 16 pound sledge and, finally, we got them [page 21] stopped. But that was an ordeal I will carry to my grave! We were taught to do things right, and there were no exceptions or excuses for failure, so that’s what we did.

Sometime during this time, I got my first bicycle. Stanley already had a bike but it was so big that there was no way I could stand up and ride it. So, I’d stick my foot through the frame and coast around for awhile. Then I got so I could stick my leg through that big frame and actually peddle that bike! What a thrill it was when I finally got my own small bike that I could straddle. We took that bike apart, took out the bearings and washed them up I think 50 times, put it all back together, set the bearing up so we could see how many times that wheel would turn (while we pushed it) before it would stop. You know, I have used that principle for setting bearings all my life ever since that day.

Now there was another thing on that place that was really something. In that beautiful park next to the house, which was fenced with a high fence, we had a big old buck sheep. He had a name but I can’t think what it was. He was really a big one. Well, in there, no~ far from the gate, was a huge log. Hey! He’d butt anything or anybody, but he was slow and big, and he would always bleat before he’d hit. We’d jump over the log, he’d run around the log, and just before he’d hit us, we’d jump back. As he went by, we could crawl on his back and hang onto that huge bunch of wool he had, and he’d go crazy trying to get us off so he could butt us to pieces.

Anyway, because Mother was sa small and we usually had men at the table, we had a hired girl. She would take in girls who needed a home and some care, so most of the year, she had these hired girls helping her. Well, it was the funniest thing! The clothesline was right next to the back door. In the corner of this park there was a big wooden gate. Every time this Swedish girl, Minnie, would go out to hang up clothes, somehow, the gate would come unlatched and here’d come this big, old buck sheep. He’d always bleat quite always before he’d hit. Anyway, when he’d bleat, she’d scream and run for the house. She never did get hit but, you know, pretty soon Mother caught on to that. Hey! Did she ever work us over when she found out we were leaving that gate latch just ajar so that when the old buck would hit the gate, it would fly open. We really caught it!

On this place, out by that beautiful double corn crib, there was a feed grinder that had a team of horses hitched to a long pole. As these horses went around and around, they would grind feed for feeding cattle. Would you believe Dad brought the feed out of the corn crib in a big basket on his shoulder, poured it into the grinder, then shoveled it out [page 22] again? Then he walked out with it to feed cattle. Imagine that, compared to the feed wagons we have nowadays! Isn’t that something? Anyway, I was so enthralled with this huge gear machine that I would stand there watching it — I knew not to put my fingers in there. I suppose I had put a stick or two in there and watched it chew them. Well, I spotted a leather tug on the ground, and I got to wondering what it would do if I put this big old leather tug in there. So, I did. The first time it made wrinkles in it, so I stuck it in again. Bang! That great big, five-foot cast gear broke and separated — flying in two different directions. Can you imagine how I felt when my Dad carne out there with the next basket of feed on this shoulder and looked down and saw that gear lying there, busted wide open? I didn’t get punished. He just looked at me and asked, “Did you put that tug in those gears?” He never did a thing, just turned around and walked back but he didn’t feed any more cattle by grinding by hand.

Just below our place, about a quarter mile, there was what was called the City Dump, but people didn’t throw dead animals or rotten garbage in there — it was things like old washing machines. Oh, the thrill of finding an old bicycle frame in there that we could put some kind of a wheel on–an iron wheel off a cultivator, or something — to run around with. That was really wonderful! We sorted through that place time and time again and we’d find some little wagon or something we could fix up and use. What an experience for little kids!

On this place, Dad had a big bunch of beautiful hogs. I mean they were dandies, but Hog Cholera hit them. Oh, what a mess. One day a huge boar came out of the barn, walking real slow, weaving around coughing. About 100 feet from the barn, he fell over. I ran out there and put my hand on his side. His heart had stopped; he was stone dead! We lost … oh, maybe all of them. It was horrible! We were supposed to burn them, but can you imagine the agony of burning 100 head of hogs?

There was a well back on the ridge, back in the field, that we didn’t use, away from anyone else or any other wells. We took the hogs back there and dropped them into the well.

We pretty near got a well full of hogs! Then we finally covered the whole thing over with dirt. An experience that a young boy will never, ever forget.

On this place, I don’t know exactly how long I was there — I was seven when I went there — but, anyway, within about a year or two, I and a little neighbor boy about the same age (I think we were in the 3rd grade) ran a trap line for several years. I ran four or five or six miles a night every night after school to check my traps. All I ever caught were [page 23] skunks and civet cats and all I ever got was 75 cents a hide. Then there was one time … we had heard about mink. Now, there really was money, a dollar or two, maybe two or three! Anyway, I caught a mink, and man, was I thrilled! But when I sent the hide in, the report came back with twenty-five cents. It was what they called a cotton mink. It had a beautiful color until you blew on the fur, and when you blew it open, instead of having a good, rich color, it was snow white.

I think I was in the 2nd grade when I came in one evening from school. I thought the fire in the big, old heater that burned hard coal, with the cylinder down the middle (it was self-fed), was out. I poked in there. There was no sign of coals, so I put some sticks and paper and stuff around the bottom and threw a can of kerosene on it. Of course, there were glowing coals down in the middle. That thing exploded, throwing the doors off the stove, blew the chimney off and out across the room, singed my eyebrows and hair. I was really a mess. It didn’t hurt me bad, but the house was horrible. To try to clean that up and put the stovepipe back on before the folks came home was really an ordeal.

Then, at the same place, I really got burned. The big, old kitchen stove had a heavy oven door, I mean it was really heavy, and adorned with bright iron. I was cold and wanted to get my feet in the oven to get warm, so I pulled a chair up by the oven. The oven door was very very hot, and I dropped it. It pinned my left hand between the edge of the chair that I was sitting on and the stove. I couldn’t get loose. I have an inch-long scar to this day. The ball of my thumb and the inside of my hand all along my thumb and all my fingers on the other hand–the tips were burned when I tried to get my left hand loose.

One evening just after dark, we were sitting out on the porch, and out of this park south of the house, we heard the old buck bleat just like he does before he hits someone. Then we heard a man yell. The old buck bleat again. The man yelled again, and then he really yelled. We heard something hit the fence away off in the far corner. You could hear that wire squeak for a mile. Pretty quick, up the driveway came Grant Bunche, the old man Dad had always had on his places. He was a heavyset man with arthritis. I guess it wasn’t the least bit funny to him, but to sit there in the dark and hear those noises and hear him yell, you knew exactly what was going on. We really got a kick out of that. He wasn’t baldly hurt but he sure was shook up.

I learned another lesson while on that place. Dad sold a bunch of hogs. The freight depot was clear through town; one block from the square in the center of the town and about five or six blocks to the depot which was on the edge of town. My [page 24] father took his boys and, instead of hauling the hogs in a wagon like everybody else in the world, he turned them out, and we drove them. We sauntered along real slow because they were fat. We drove that herd of hogs, probably about 200, right down the street. Everybody from allover the country came out to watch the procession. I remember that it was really embarrassing to me but it didn’t seem to bother my dad a bit. We drove them down there, walking real slow, and they weren’t all beat up from loading and pounding around — just let them take their time and grunt along. They arrived at the stockyard in perfect shape.

There were two huge livery barns in town. On was exactly one block west of the square, right in town. It was a gigantic affair. I don’t know whether the fires were set for insurance, or not but this big thing caught afire, and we could hear the noise, sirens or bells, in the middle of the night. There was a ruckus; people hollering. We could see the flames, and I guess they were several hundred feet high. We were about four blocks from that fire, and the heat was so intense that there were whole shingles in the air that actually fell in our yard, and we had to watch to see they didn’t set things afire around our barns. Eventually, the other livery barn burned, although I don’t remember that fire. It was only a half-block from the corner of the center of the square in town.

It was here in 1913, our first year on this place, that we got to go to the County Fair, and I saw my first airplane. It was freighted from the old depot a mile out of town, clear through town, and to the fairgrounds, with a horse dray, in wooden crates. It was opened up and assembled there, and it flew! In fact, it flew all over the country, around and around, and it did a good job. That was a real event, seeing that plane flying and doing a good job.

The other big event on this place — I don’t know if I was 13 or 15, but someone in our family had died up in the northern part of Iowa. My mother and dad got on the train. Of course, we boys were big enough to do the chores and take care of the livestock. This huge barn had a runway clear around three sides of it with 16-18 foot gates. You could put the gates against the walls and then it was all open, or you could swing the gates around to the center and you had 15 or 20 pens. Wouldn’t you know — I don’t know if I had ever seen or heard of a rodeo but of course, everybody rode calves; we all knew that. Anyway, we put the gates all back against the side of the barn and ran a bunch of stock cattle in there. They were mostly yearlings and two-year-olds. In the bunch was a great, big high-horned heifer. She stood about two feet above the rest of them. We hung a lantern up at each end of the [page 25] barn, and discovered if we could run those cattle off to one end and hold them there all bunched up tight, we could jump up and run right across the whole bunch and pick out the one we wanted to ride. Then, when they untangled and ran back, we got a free ride clear across to that barn, wide open!

Man, we were having a ball! We were really the cowboys. Now of course, all couldn’t go smooth. I got up there running across their backs and here was this great big, high-horned heifer, right smack in front of me. Like a darned fool I straddled her. When they untangled, she exploded! I rode her down to the other end of the barn where she whammed me up into the rafters. I came down on my back across toe edge of a cement gutter with a sharp edge, about a 16″ trough. I couldn’t walk. Would you believe, my brother knelt down beside me in the dirt and the first thing he did was to put me under oath! “No matter what happens — I don’t care WHAT happens — you are NOT going to tell the folks what we were doing!

Well, I rolled around there for awhile. Talk about back injuries! A few years later, after we had moved into town, I was walking to town; in fact, I was a little late and was running to school. We had a brand, new asphalt pavement with sidewalks, curbs, and cement gutters. It was a cold morning. I had to cross the street. I crossed it at an angle, and there was a Model-T Ford several blocks away. There wasn’t another car within miles of us. I crossed over the pavement and was running down on this new, white, sidewalk-like curb, next to the curb. This car came down the road from several blocks away, not slacking up one bit. It didn’t go by me, it went along the edge of the curb, slammed into me, hit me in the back, and threw me on my face, and ran over me!

Now, I can’t account for how I did this or how I had brains enough for it, but those Model-T Fords had a V-wishbone in front, and my feet flew up, got caught in that V-wishbone–I was on my stomach — and somehow, I twirled around sideways rather than have that pull my feet up over my back and break my back. When the car stopped over me, my feet were caught in this wishbone. I missed the front wheel. My face was right under the left door. An old white-haired woman fumbled around for her gloves and peeked out through the side curtain and she said, “Oh! I just tried and tried and tried to find that horn, but I just couldn’t find the horn.”

This was an old woman who drove her daughter out into the country to teach school, and I guess she drove her every day. Well, about a month after this had happened, we were driving cattle out of town and we saw this old woman come down a long hill. There was a hay rack on the road but she didn’t go by the hayrack, she ran up behind it and slammed into it. She [page 26] smashed her radiator and all the water ran out onto the ground. How could any person on earth do that? But, that is what the old, white-haired lady did.

Somewhere about this time–1913, 1914, or ’15–we had a bad drought. The pastures turned brown in June. We drove the cattle from this Duncan Place about two miles north and five miles west to the Nodaway River where I used to trap. We did that for weeks and weeks. We let them graze down the road, slowly going and slowly coming back. Most of the wells around the country dried up. Our well was really dry. That river finally dried up~ and I can remember the last big hole on that river had only about eighteen inches of water in it There were lots of catfish in there. I was always putting catfish in the bottom of the buggy–didn’t have a bucket. I brought them home and put them in the stock tank where some of them revived, at least for a few days, and swam around the stock tank.

I’ll always remember the Sunday our dog got hit. I thought he was killed. He layout in the weeds alongside of the road, but when we came back about two days later, and here was this big, gangling, half-Collie and half-Fox Terrier pup, alive and running around waiting for us. I don’t know how he lived, but he did.

JC was born in 1914 in a town called Crescent, Iowa, twenty miles south of us. We went down by railroad many times, sometimes by railroad and sometimes by car. Anyway, Mother went down to this hospital quite a bit before her time. There was a good doctor there and the hospital. She had had some horrible times delivering before. I remember before she went to the hospital, she was rushing around one Sunday morning, trying to get us off to Sunday School and she fainted–sprawled out on the floor. Dad came in, picked her up, and carried her to the bed. I had never seen Mother faint before, and I couldn’t understand this. I don’t remember what they told us about having babies. I can’t remember whether we looked forward to the event or if we were kept in total ignorance.

Anyways, JC was born. Away back in the original history, I have a file, and in it is a copy of that hospital bill. You can’t believe how cheap the costs were:

Cottage Grove Hospital, A.J. Pemberton, ten days at $2.50 per day. Total bill: $25.00. Two weeks at $20.00 = $40.00. Nurse’s board and room, $5.00 per week. Telephone calls: Mr. Pemberton’s bed, 75 cents. Mrs. Cora’s bed, 75 cents. Total bill: $84.25.

There were two doctors who worked on the case. Each visit was [page 27] one dollar, and the one time, of course, it was $15.00. I guess his companion charged $10.00. The total bill was $28.00. It’s hard to account for that in 1982!

In 1914, I was eight years oldi maybe I came nine that summer. Anyway, Dad had some land out at Council Bluffs, a hundred miles west on the Missouri River bottom. We took horses, wagons, supplies, and that old Willys Knight. Incidently, Stanley drove that Willys Knight. In fact, he drove that car allover the state of Iowa, for Dad, when he was fifteen or sixteen years old. Never heard of a drivers license. I remember he had to hold on to the ~teering wheel and stiffen his body clear out to push his leg down on the brake and the clutch to operate it. I don’t know why he didn’t make a block to put behind his back. Well anyway, Dad had a swell hired man by the name of John Reese, and they drove those horses and wagons a hundred miles, to Council Bluffs. Of course, I got to ride with Mother and Stanley in the old Willys Knight with all our supplies and our cooking utensils. Mother was an artist at camping and “make-do”.

We’d set up a tent ‘way back from anybody’s house. Snakes! There were bull snakes in there, eight feet long. Would you know, Mother took some old hens with her–even had an old hen with little chickens to keep her busy! I drove buckrake. I was eight years old, and I drove the team to the buckrake all that summer. I think the team I drove was Steve Jackson’s beautiful bay Morgan horses. I can’t remember whether Steve was with us or not. All I remember was this John Reese who fished the hay up to Dad. Dad was always on the stack. Everything was hand work. This buck rake was a wide rake with great, long teeth that slid under the hay in windrows, a horse out on each side. I would bring that hay in, up to the stack, and back away, tipping the rake out from under it, and go back for another load. Snakes! You can’t believe the bull snakes. There was what they call the Red Adder there. It wasn’t poisonous. It looked like a Garter Snake except it was real thick with a blunt tail and a white mouth. They could sit up and hiss and raise holy Cain. Here I was, an eight year old kid, probably barefoot, and in every load I brought, I would see snakes drop out of it.

I remember one time there was a great, big bull snake. I had seen him in that load two or three times. He would stick his nose out and then go back in. Man! I was standing up in the seat. I jerked the horses back and I says, “That thing is full of snakes–there’s a dozen snakes in there!” The man that fished out on the stack was a great, big muscled guy. He pitched that hay up there and on the last forkful of hay, as Dad reached down to take the hay from him, here came a giant bull snake, down around the pitchfork [page 28] handle, down around the back of the guy’s neck. Old John just turned around, whopped him with the pitchfork, and threw him up in the pile with the other snakes, and there I was just a’screaming bloody murder.

I have a picture of myself and three of the neighbor kids, one I started trapping with when I was seven or eight years old. When I look at that picture, there is no way I can make myself believe that I went clear across country, up and down that river, and trapped for a year or two. We had to run. If we didn’t, it would be pitch black and we’d have a horrible time getting out. Of course, many times it WAS pitch dark. The thing that really got to us were the doggoned dogs along the road.

One night we had finished trapping and had just come up over the hill. We’d skirted this farmhouse, a half or quarter mile, and were just ready to cut across an open field. There were two dogs. One was Collie and one was part Bulldog or something. They were so ugly and they really raised Cain. Of course, we went across to the opposite side of the road, climbed the fence, and started to cross the field. We got about halfway across the field when those two dogs came at us, their mouths wide open, ready for blood. We had our hands full of traps and probably a stake or something–no gun, no nothing to hit them with. We stopped and stood still, back to back, with the traps in front of us and eased our way an inch at a time. I’ll be darned. I was petrified with fear. I didn’t figure we’d ever get away from those dogs, but finally–it must have been a full hour–they gave up.