This website was hacked and all avenues for data to enter the site have been closed in order to provide maximum protection of members’ information. The menus are only partially functional but all the content is still here. However, much of it can only be found when you use the search box on the right. We expect to have the site fully functional again this year, 2022. Meanwhile, if any of you know a Pemberton enthusiast who knows how to use WordPress web publishing, please – we could use some help here.

This website was hacked and all avenues for data to enter the site have been closed in order to provide maximum protection of members’ information. The menus are only partially functional but all the content is still here. However, much of it can only be found when you use the search box on the right. We expect to have the site fully functional again this year, 2022. Meanwhile, if any of you know a Pemberton enthusiast who knows how to use WordPress web publishing, please – we could use some help here.

Jackson Pemberton, President

president@pembertonfamily.com

Pemberton Heraldy

The Pemberton Griffin

The griffin is perhaps the oldest crest used by the Pembertons. The two-inch miniature pictured here is a finger-sculpted ceramic by Madeline Pemberton. She crafted it during the 2012 Pemberton Family Reunion as a three-dimensional replica of the image on a T-shirt pictured below. For a great array of merchandise emblazoned with a Pemberton arms, take a look here: https://coadb.com/surnames/pemberton-arms.html.

A Common Misconception

It seems appropriate to first of all address a most common error: that a surname has a coat of arms associated with it. This error is perpetuated by the “bucket shop” coats of arms vendors, who, for a price, will gladly plagiarize a coat of arms from a family rightfully possessed of it and give it to another. Another source of the misunderstanding is that arms could be and still are inherited thus staying in a surname lineage. In many families, the coat of arms was carefully passed down to those sons whose proper demeanor qualified them for this honor. In more modern times, the “younger generation” never quite seeing things are their parents, have taken upon themselves to inherit their ancestors’ arms that were technically not theirs, not autorized by the parent(s) who held them with authority.

So in a looser sense, one may say there is a de facto coat of arms for a particular lineage. Still, there may be other arms or coats of arms within a family line that are quite different; the changes being made by choice, marriage, or the award of some honor.

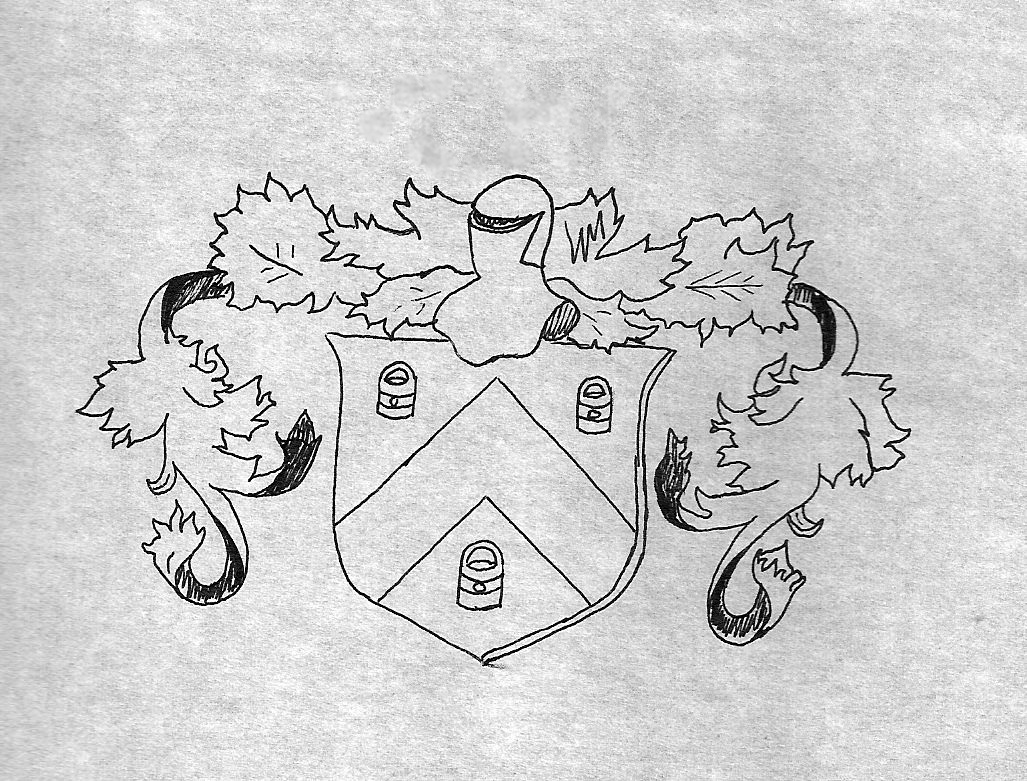

Finally, in the case of the Pemberton family, most coats of arms seem to have a characteristic chevron with three buckets. The earliest arms of Pembertons, however, were emblazoned with griffins where the buckets later appear. These arms are treated later.

Heraldry

First it is important to understand that heraldry is not just a historical phenomenon, but is very much alive and well with living Heralds and Kings of Arms. Ancient governmental organisations still function today as the official keepers of all things heraldic, with the English College of Arms in London being the one of interest to the Pemberton family. Their website states: “Coats of arms have been and still are granted by Letters Patent from the senior heralds, the Kings of Arms. A right to arms can only be established by the registration in the official records of the College of Arms of a pedigree showing direct male line descent from an ancestor already appearing therein as entitled to arms,…” For those interested in the artistic side of heraldry, here is a short essay on Heraldry as Art.

To understand the word heraldry, a little history is very useful. Here is a quote from the website College of Arms Foundation, Inc., the official American outpost of the English College of Arms:

Heralds are first mentioned in the historical accounts about the time of the first crusade (ca. 1100). By the late 12th century their importance had grown, coinciding with the development of sophisticated armor for knights. At that time, distinctive markings easily distinguishable from a distance were essential for recognizing combatants whose faces were fully covered by helmets. These markings were placed on surcoats worn over the armor (the derivation of the term coat of arms) and were passed down from father to son, with families becoming identified by the markings. It was the responsibility of the heralds, who also served as military staff officers, diplomats and messengers (they were often the only members of a household who could read), and masters of ceremony at pageants and tournaments (where they were allowed to keep any broken armor), to keep track of which family used which emblems and ensure that the emblems were distinct from one another. Because the coats of arms were hereditary, the herald’s expertise has long covered lines of descent.

Armory, Armoury, Heraldry, Coats of Arms, Devices, Charges and Crests

These are words familiar to many, but often greatly misunderstood and often incorrectly used interchangeably. All these are intertwined by history, by usage and by customs in England and indeed all of Europe. A change in any of them would influence the others. They find their origins as statements of honour, wealth, power, and military might. And, of course, all of those are near cousins to one another. “Arms” in its most specific sense refers to the shield device. Arms were connected with weapons and for a time “Coat Arms” was a name for insignia sewn into the coats of military men worn over their armor. We still see this concept on present day military uniforms where a patch or badge identifies the military unit to which the wearer belongs.

There is considerable misunderstanding on this subject, so an appeal to the supreme authority is appropriate. There is a wonderful diagram of a “full achievement of arms” (showing what devices are named and where they are placed) on the official website of the English College of Arms [not a university] in London, England. You should proceed to this link (it will open in a new window) and study it to make the rest of this discussion much more illuminating. You will need to scroll down a little to see the diagram labelled “The Design of the Arms”. Here is the diagram.

The entire subject is a complex one, and no brief treatment of it can be complete. Furthermore, a brief treatment of such a complex subject will necessarily be somewhat misleading. Nevertheless, everyone is curious about these matters so we will make a guarded attempt to address the subject here. In A Complete Guide to Heraldry, by Arthur Charles Fox-Davis, London, 1909, we read the following about armory and arms:

Armory is that science of which the rules and the laws govern the use, display, meaning, and knowledge of the pictured signs and emblems appertaining to shield, helmet, or banner. Heraldry has a wider meaning, for it comprises everything within the duties of a herald; and whilst Armory undoubtedly is Heraldry, the regulation of ceremonials and matters of pedigree, which are really also within scope of Heraldry, most decidedly are not Armory.

“Amory” relates only to the emblems and devices. “Armoury” [Editors Note: watch the spelling of these words.] relates to the weapons themselves as weapons of warfare, or to the place used for the storing of the weapons. But these distinctions of spelling are modern.

The word “Arms,” like may other words in the English language, has several meanings, and at the present day [1909] is used in several senses. It may mean the weapons themselves; it may mean the limbs upon the human body. Even from the heraldic point of view it may mean the entire achievement, but usuallly it is employed in reference to the device upon the shield only.

Of the exact origin of arms and armory nothing whatever is definitely known, and it becomes difficult to point to any particular period and the period covering the origin of armory, for the very simple reason that it is much more difficult to decide what is or is not to be admitted as armorial.

Until comparatively recently heraldic books referred armory indifferently to the tribes of Israel, to the Greeks, to the Romans, to the Assyrians and the Saxons; and we are equally familiar with the “Lion of Juda” and the “Eagle of the Caesars.”

Coats of Arms

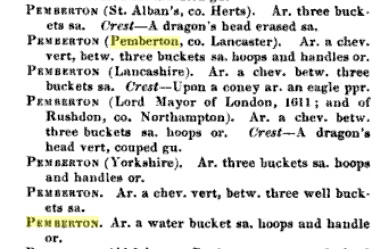

Pictured here is a short segment from the book Encyclopedia of Heraldry: or General Armory of England, Scotland, and Ireland, John Burke, Esq., London, 1844.

The abbreviations are a bit daunting, but we believe the first entry reads as follows:

Pemberton (St. Albans [a town 22 miles north of London] in the county Hertfordshire. Arms three buckets sable. Crest – A dragon’s head erased sable.

These armorial bearings were undoubtedly those of Sir Francis Pemberton (18 July 1624 – 10 June 1697) who was an English judge and briefly Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench.

Some of the abbreviations refer to colours or “tinctures” as they are called in heraldry: sable (black), Gules (red), Or (gold), Vert (green), Azure (blue), Purpure (purple) Argent (white or silver), Tenne (orange), and Sanquine (crimson).

It is interesting that all these describe arms with a chevron and three buckets, except the last one which describes a single “water bucket” and no chevron. Ususally the buckets are hooped (strapped around with one or more belts to hold the wooden staves in place) and have handles.

Another arms description is found in A History of Shrewsbury, Vol. 2, by Hugh Own, page 296:

A. a chevron between three buckets S. hooped O.

This reads thus: The arms are a chevron between three buckets, with the buckets colored Sable [black] and hooped [bands around the wooden staves], the hoops are colored Or [gold].

The arms of the famous Confederate General John C. Pemberton, are described in the book Early New England people : some account of the Ellis, Pemberton, Willard, Prescott, Titcomb, Sewall and Longfellow, and allied families. Boston: W.B. Clarke & Carruth, c1882, thus:

Argent, a chevron, sa. between three buckets of the second, hooped and handled or.; crest, a dragon’s head, couped sa. erect.

Quoting again from a previous book (A Complete Guide to Heraldry) , we find the following on Coats of Arms:

It would be foolish and misleading to assert that the possession of a coat of arms at the present date [1909] has anything approaching the dignity which attended to it in the days of long ago; but one must trace this through the centuries which have passed in order to form a true estimate of it, and also to properly appreciate a coat of arms at the present time. It is necessary to go back to the Norman Conquest and the broad dividing lines of social life in order to obtain a correct knowledge. The Saxons had no armory, though they had a very perfect civilisation. This civilisation William the Conqueror upset, introducing in its place the system of feudal tenure with which he had been familiar on the Continent. Briefly, this feudal system may be described as the partition of the land amongst the barons, earls, and others, in return for which, according to the land they held, they accepted a liability of military service for themselves and so many followers. These barons and earls in their turn sublet the land on terms advantageous to themselves, but nevertheless requiring from those to whom they sublet the same military service which the King had exacted from themselves proportionate with the extent of the sublet lands. Other subdivisions took place, but always with the same liabillity of military service,.. Every man who held land under these conditions – and it was impossible to hold land without them – was of the upper class. He was nobilis or known, and of a rank distinct, apart, and absolutely separate from the remainder of the population, who were at one time actually serfs …This wide distinction between the upper and lower classes, … was the very root and foundation of armory.”

Devises and Charges

The chevron is one of the common devices displayed on many coats of arms. It is a french word meaning rafter and portrays a common peaked roof. The symbolism is of protection. The bucket, the most consistent or constant devise in Pemberton arms, is a water or well bucket, and most likely came from a Pemberton who provided water for combatants or for a beseiged community. Pemberton arms (the shield) are typically “charged” with a chevron and water buckets. For those wishing more information about the various devises used to charge arms, here is a good reference website.

The Three Buckets and the Three Dragons

Almost all Pemberton arms contain three buckets, nearly always hooped and handled, displayed around a chevron. The heraldryandcrests.com website says that it “was conferred on those who had supplied water to an army or a besieged place. The bucket is merely the more modern way of transporting water. The common well bucket is usually the type born in arms, but they can also be hooped or have feet.” We do see feet on some Pemberton buckets. Their description of the use and meaning of the barrel devise is also interesting: “Barrels, or casks, were commonly used to hold beer or wine. It possibly symbolizes that the original bearer was a vendor of beer or wine, or an innkeeper. It occurs in the insignia of the BREWERS’ and VINTNERS’ Companies, as well as in the arms of a few families. It is often used as a pun on names ending in ‘ton,’ for example the crest of Hopton depicts a lion hopping on a tun. Also known as “Tun”. The tradition that the word Pemberton originated from something like a barley field on a hill can be tied in with barrels to hold the barley beer, if one is speculating on connections between all these things.

A Pemberton arms of particular interest was found in Warwickshire and was claimed to be one of the first 50 arms granted after the Normans came to England. It displays three dragons, each placed where the buckets are usually found. Indeed nearly half the coats of arms found in the book Pemberton Pedigrees contain both buckets and dragons.

The Crest

The crest is the device above the shield in the coat of arms. The College of Arms, London has this to say about the crest: “It is a popular misconception that the word ‘crest’ describes a whole coat of arms or any heraldic device. It does not. A crest is a specific part of a full achievement of arms: the three-dimensional object placed on top of the helm.”

Again we quote from A Complete Guide to Heraldry:

If uncertainty exists as to the origin of arms, it is as nothing to the huge uncertainly that exists concerning the beginnings of the crest. Most wonderful stories are told concerning it; that it meant this and meant the other, that the right to bear a crest was confined to this person or the other person. But practically the whole of the stories of this kind are either wild imagination or conjecture founded on insufficient facts.

The real facts – which one may as well state first as a basis to work upon – are very few and singularly unconvincing, and are useless as original data from which to draw conclusions.

First of all we have the definite, assured, and certain fact that the earliest known instance of a crest is in 1198, and we find evidence of the use of arms before that date.

The next fact is that we find infinitely more variation in the crests used by given families than in the arms, and that whilst the variation in the arms are as a rule trivial, and not affecting the general design of the shield, the changes in the crest are frequently radical, the crest borne by a family at one period having no earthly relation to that borne by the same family at another.”

One can see a number of “Pemberton Crests” at the MyFamilySilver website. Click on the “Crest Finder” tab in the upper corner and enter Pemberton into the search box.

Pemberton Coats of Arms

Technically, as pointed out in the opening paragraph of this essay, there is no such thing as the Pemberton Coat of Arms. That is because a particular design does not belong to any Pemberton who is not of the lineage to which the arms were awarded. However, the number of arms attached to persons of Pemberton descent are very few and seem always to have three buckets and a chevron as depicted below.

However, the Surname Database states that “The earliest arms have the blazon of a silver shield, a chevron ermines between three black griffins’ heads couped.” Indeed, some of the arms in the PFWW library are three griffins instead of the more familiar buckets.

The Pemberton Family World Wide has over a dozen Pemberton coats of arms in its library. These are only available to members of the PFWW. To become a member, select “Become a Member” in the Site Access menu.

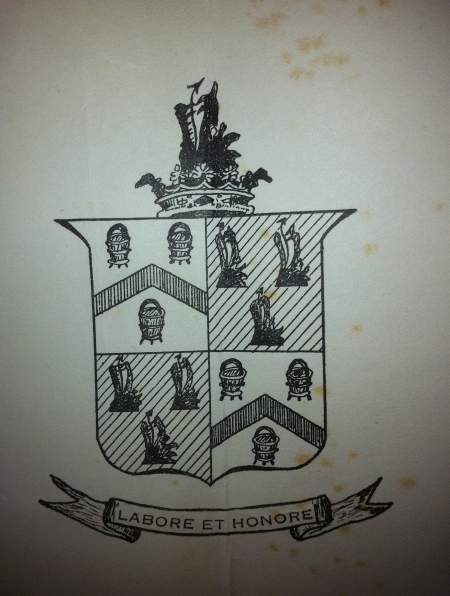

The coat of arms below has the following description associated with it. [Note that the italicized words are rendered exactly as in the description and are typical of such descriptions.]

Family of Dr. Thomas Pemberton, New Zealand.

Arms: Quarterly 1st and 4th Argent, a Chevron between 3 buckets sable, hooped and handled or, 2nd and 3rd argent, 3 dragons’ heads sable. Crest: A dragon’s head erect sable. Motto: Labore et honore.

If you know some reliable information on this topic or pictures of other Pemberton arms or crests, please email thepresident@pembertonfamily.com.

Authoritative Texts on Heraldry

America Heraldica: A compilation of Coats of Arms, Crests and Mottoes of prominent American Families settled in this country before 1800 (Vermont, E de V, 1886)

Crests of the Colonial Gentry (Knight and Butler)

Armorial Families (Fox Davies, A C; 1929)

Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry (1939 ed.)

Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage and Gentry

Fairbairn’s Book of Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland (Fairbairn, James; 1905 ed.)